The concept of acceleration due to gravity has fascinated scientists, students, and thinkers for centuries. It’s the invisible yet powerful force that shapes our world—causing an apple to fall, keeping oceans grounded, and guiding planets in their endless dance around the sun. Represented by the symbol ‘g,’ this natural constant defines how objects accelerate when pulled toward Earth’s surface. Though often simplified as 9.8 m/s², its importance reaches far beyond a single number—it forms the foundation for physics, engineering, and even space exploration.

The Science Behind Acceleration and Gravity

Gravity is one of the four fundamental forces of nature. Unlike electromagnetic or nuclear forces, which dominate at microscopic scales, gravity governs massive celestial structures—from falling stones to galaxies. The term acceleration due to gravity refers to the rate at which an object’s velocity increases as it moves toward Earth’s center. In physics terms, it’s the measure of Earth’s gravitational influence on a body’s motion.

Scientists define it mathematically as:

[ g = \frac{F}{m} ]

Here, (F) represents the gravitational pull experienced by an object, while (m) denotes its mass influencing that force. Near the Earth’s surface, this produces an acceleration of approximately 9.81 m/s². Though that figure may seem constant, it subtly varies depending on location, altitude, and Earth’s rotation.

The Gravitational Constant and Universal Attraction

To truly understand acceleration due to gravity, we look to Newton’s Law of Universal Gravitation. Newton discovered that every two masses attract one another with a force directly proportional to their masses and inversely proportional to the square of the distance between them:

[ F = G \frac{m_1 m_2}{r^2} ]

Here, (G) represents the universal gravitational constant (6.674 × 10⁻¹¹ N·m²/kg²), (m_1) and (m_2) are the two masses, and (r) is the distance separating them. When this equation applies to Earth, it explains why all objects fall at the same rate regardless of their mass—because the acceleration, (g), depends only on Earth’s mass and radius, not the object itself.

The Mathematical Derivation

If we combine Newton’s law and the relationship between force and acceleration, we derive:

[ g = G \frac{M}{R^2} ]

where (M) is Earth’s mass and (R) is its radius. Substituting known values for (G), (M), and (R) gives the familiar 9.8 m/s². This calculation shows that gravity results from the immense mass of Earth exerting force over an enormous distance.

Factors Influencing Gravitational Acceleration

Even though the canonical value is 9.8 m/s², gravitational acceleration varies slightly across locations due to several factors.

1. Altitude

As you move away from the Earth’s surface, the distance between you and Earth’s center increases. Because gravity weakens with distance, g decreases slightly at higher altitudes. This explains why astronauts in orbit experience microgravity.

2. Latitude

Earth’s rotation and slight bulging at the equator alter gravity’s pull. Gravitational acceleration is stronger at the poles (around 9.83 m/s²) and weaker near the equator (around 9.78 m/s²).

3. Geological Composition

Mountains, ocean trenches, and density variations beneath Earth’s crust create minor fluctuations in local gravitational strength. Modern gravimeters can detect these small differences and are used for geological mapping.

These variations might be imperceptible in daily life, but for physicists and engineers, they are crucial for accurate calculations in navigation, surveying, and satellite motion.

The Legacy of Discovery

The story of acceleration due to gravity begins with Galileo Galilei in the 16th century. Through his famous inclined‑plane experiment, he observed that objects, regardless of mass, accelerated at the same rate when friction was negligible. This discovery shattered centuries of Aristotelian belief that heavier bodies fall faster than lighter ones.

A few decades later, Isaac Newton provided the mathematical framework to explain Galileo’s observations. His laws unified the movement of celestial bodies and falling objects under a single principle of universal gravitation. Centuries afterwards, Albert Einstein expanded this concept with his General Theory of Relativity, redefining gravity as a curve in spacetime created by mass. According to Einstein, the 9.8 m/s² we experience on Earth isn’t a pull, but the natural path (geodesic) objects follow through curved spacetime.

Together, these thinkers helped us move from mystical explanations of falling objects to a deep understanding of the law that binds the universe together.

Measuring Gravitational Acceleration on Earth

Scientists have devised several experiments to measure g accurately. The free‑fall method involves measuring how quickly an object’s velocity increases as it drops from a known height. Using sensors or precise timing equipment, this approach can determine local variations to a very fine degree.

The simple pendulum method remains another classic experiment. The time it takes for a pendulum to complete a full swing depends directly on gravity. By adjusting the pendulum’s length and timing its oscillations, we can calculate g using the formula:

[ g = \frac{4\pi^2 L}{T^2} ]

where (L) is the pendulum’s length and (T) is its period.

In recent years, sophisticated instruments like gravimeters and laser Doppler devices have allowed measurement accuracy up to micro‑level variations. These instruments contribute to geophysics, meteorology, and even oil exploration.

Practical Implications in Daily Life

Gravity’s acceleration affects nearly every human activity even if we don’t notice it. Engineers account for it when designing bridges, ensuring safe load bearing. Architects use gravitational calculations to determine building stability. Every athlete’s trajectory, every rocket launch, and every waterfall is determined by gravity’s unchanging influence.

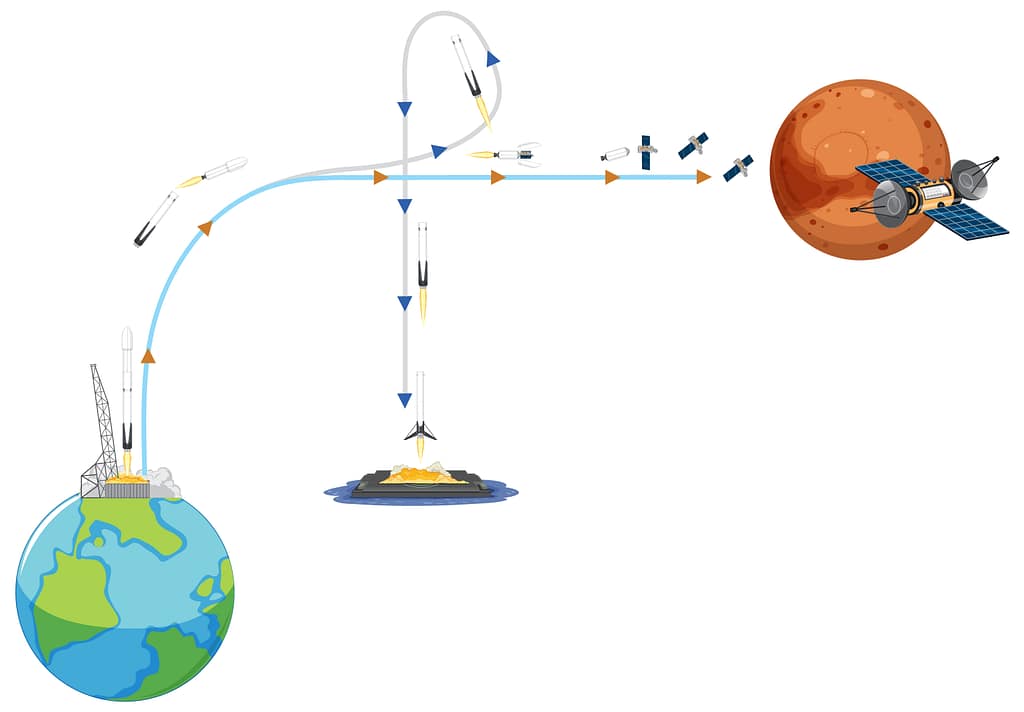

In aerospace engineering, precise knowledge of gravitational acceleration enables the prediction of flight paths and orbital mechanics. Satellite systems depend on accurate gravity models to maintain stable orbits. Even smartphones employ gravitational sensors for screen orientation and motion tracking.

Without understanding g, modern technology—from elevators to GPS systems—would not function with the precision we rely on today.

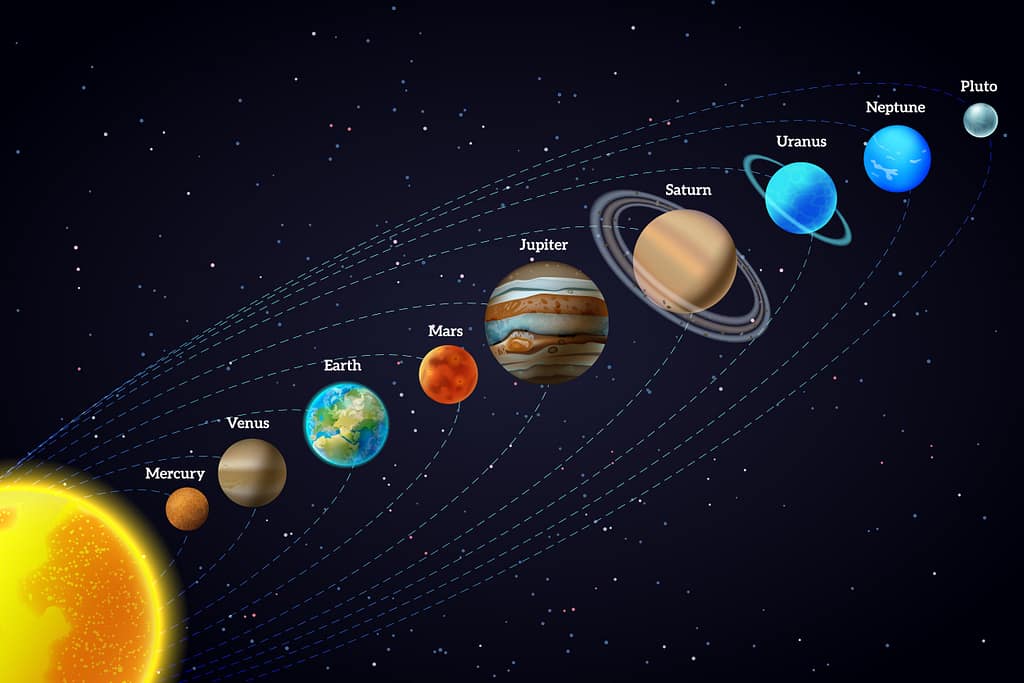

Beyond Earth: Gravity Across the Solar System

The value of g differs widely across planets. On the Moon, it’s about 1.6 m/s²—just one‑sixth that of Earth, allowing astronauts to take large moon‑hops. On Mars, it’s 3.7 m/s², while Jupiter’s towering mass exerts a g of about 24.8 m/s². These differences dramatically influence planetary atmospheres, escape velocities, and potential habitability.

Future missions to Mars and beyond depend on understanding how gravity differs from Earth’s. Equipment, habitats, and vehicles must all be adapted for lower or higher gravitational conditions to ensure safety and performance.

Common Misconceptions About Gravity

Many still think that gravity requires atmosphere or air. In reality, air resistance merely slows falling objects—gravity acts equally in a vacuum. Another misconception is that astronauts in space are “beyond gravity.” In fact, they’re continuously falling around Earth, their sideways motion perfectly counterbalancing the downward pull, creating the sensation of weightlessness.

These concepts highlight why gravitational acceleration is more than an Earth‑bound curiosity—it’s a universal principle.

Conclusion

In summary, acceleration due to gravity is one of the most essential constants in nature. More than a number memorized in textbooks, it’s an ever‑present phenomenon shaping how objects move, planets orbit, and energy interacts. From Galileo’s discoveries to Einstein’s relativity, our understanding of g has grown from simple observation to the foundation of modern physics.

Every time you drop an object, see a satellite in the sky, or watch a waterfall plunge, you’re witnessing the profound elegance of this invisible force. The beauty of g lies in its simplicity—it defines motion across the universe, reminding us that gravity isn’t just a pull from Earth but a bond connecting everything that exists.